Summary to the difference between T and T* method sets in Go

TL;DR

Many – including me – regularly get confused by the inability to use pointer receiver methods on value interfaces. There are several levels of explanations available: from so called “Method sets”, which do not actually explain the root of the behavior, to more complicated like “Addressability”. Answers and useful pointers are scattered over the Internet both spatially and in time (this became a common stump for Go learners as early as Go appeared). In this post, I try to summarize the learnings of why sometimes one can use Go’s syntactic flexibility when calling methods – and sometimes not.

The post narrates the story as a series of short showcases, so for those understanding the problematic and coming here for answers – please fast-forward to attempts to answer.

NOTE: code is available on Github

Outline

Methods and their receivers

In Go, methods are not semantically bound to the enclosing structures. As such, one declares them using the construct of

receiver, which is the object on which the given method will

be called. Loosely speaking, it is an analog of self in Python or this in C++.

On can define a method with receiver of

- a pointer type: in this case the method should be called on the pointer and can modify it;

- or a value type: in this case the method is called on a copy of the object which calls it.

// Pointer type receiver

func (receiver *T) pointerMethod() {

fmt.Printf("Pointer method called on \t%#v with address %p\n\n", *receiver, receiver)

}

// Value type receiver

func (receiver T) valueMethod() {

fmt.Printf("Value method called on \t%#v with address %p\n\n", receiver, &receiver)

}

Calling those methods canonically would then happen like that:

var (

val T = T{}

pointer *T = &val

)

fmt.Printf("Value created \t%#v with address %p\n", val, &val)

fmt.Printf("Pointer created on \t%#v with address %p\n", *pointer, pointer)

val.valueMethod()

pointer.pointerMethod()

This will print the following (note change in address for calling method by the value receiver - copy of the object is passed):

Note that to get this one needs that T is not empty struct1:

➙ go run main.go

Value created main.T{i:0} with address 0xc0000180b2

Pointer created on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc0000180b2

Value method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc0000180e0 # note a copy is created

Pointer method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc0000180b2

How methods can be called on various receivers

What may confuse (or fascinate, depending on the mood) newcomers to Go, especially those coming from strictly-typed languages like C++, arises from a syntactic-sugary ability of the Go compiler to automatically dereference pointers, as well as automatically take value address. Both statements below are thus valid, too:

pointer.valueMethod() // Implicitly converted to: (*pointer).valueMethod()

value.pointerMethod() // Implicitly converted to: (&value).pointerMethod()

which produces the expected output

Pointer method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc0000180b2

Value method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc000018110 # note another copy is made

At this point, let’s make an important snapshot of how the user experience “which methods can one call - and on what” looks like:

| Method receiver type | On what objects can be called directly |

|---|---|

T | both T and *T |

*T | both T and *T |

All the four combinations work!

NOTE: If you are interested in a deeper dive into the Go language Specs, here’s the excerpt which tells which two mechanisms actually allow you to automatically dereference/take the address of the calling object:

As with selectors, a reference to a non-interface method with a value receiver using a pointer will automatically dereference that pointer:

pt.Mvis equivalent to(*pt).Mv.As with method calls, a reference to a non-interface method with a pointer receiver using an addressable value will automatically take the address of that value:

t.Mpis equivalent to(&t).Mp.— From Specs#Method_values

Interfaces

Next, a newcomer to Go typically learns about interfaces. An interface in Go is a separate type which represents a

set of methods. Just as methods, interfaces are semantically decoupled from types which implement them. In other words,

when a struct T is defined, there’s no indication that it wants to implement some interface:2

type ValueMethodCaller interface {

valueMethod()

}

// No indication that struct `T` intends to implement `ValueMethodCaller` interface

type T struct {

// ...

}

func (receiver T) valueMethod() {

// ...

}

This is sometimes called structural typing, in contrast to nominal typing (like C++) and duck typing (like Python).

As Ian Lance Taylor puts it (italic mine):

Interfaces in Go are similar to ideas in several other programming languages: pure abstract virtual base classes in C++; typeclasses in Haskell; duck typing in Python; etc. That said, I’m not aware of any other language which combines interface values, static type checking, dynamic runtime conversion, and no requirement for explicitly declaring that a type satisfies an interface. The result in Go is powerful, flexible, efficient, and easy to write.

A canonical way to call methods on interfaces is thus (all the definitions are simple and can be found on Github)

func callValueMethodOnInterface(v ValueMethodCaller) {

v.valueMethod()

}

func callPointerMethodOnInterface(p PointerMethodCaller) {

p.pointerMethod()

}

// ... Later in main()

var (

val T = T{}

pointer *T = &val

)

callValueMethodOnInterface(val)

callPointerMethodOnInterface(pointer)

which produce, expectedly

Value method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc000018121

Pointer method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc0000180b2

How methods can be called on interfaces

At this point, a newcomer to Go starts getting into an experimental mood, encouraged by the compiler’s smartness and and its ability to convert value-pointer pairs on the fly. She tries:

callValueMethodOnInterface(pointer)

and it works! The value method is called on a copy of the object:

Value method called on main.T{i:0} with address 0xc000018140

The compiler seems to figure out that the pointer is compatible with ValueMethodCaller interface - and after all the

learnings from above, there’s no surprise!

The experimentation continues, one tries the vice-versa setting of calling pointer method on a value through the interface (from the above learnings, there’s an impression it should work, too)

callPointerMethodOnInterface(val)

Bang! Instead of the expected message, one gets a cold complaint from the compiler:

./main.go:64:19: cannot use val (type T) as type PointerMethodCaller in argument to callPointerMethod:

T does not implement PointerMethodCaller (pointerMethod method has pointer receiver)

Sounds like out of four possible combinations (to remind: two options for the receiver type and two for the calling interface), this is the only one which does not compile. So, similar to the table above (representing a summary of “which methods can one call - and on what”), let’s make the second table representing a summary of “which methods can one call – and on which interfaces”:

| Method receiver type | On what objects can be called via interface |

|---|---|

T | both T and *T |

*T | only *T |

So what is the difference and why does this happen at all? Let’s describe both more formal and less formal answers.

Method set of a type prevents calling pointer method on value interface

Formal answer to the “why”-question above lies somewhere around the definition of method sets from Go Language Specs

The method set of any other type T consists of all methods declared with receiver type T. The method set of the corresponding pointer type *T is the set of all methods declared with receiver *T or T (that is, it also contains the method set of T).

— From Go Specs#Method_Sets

The illustration of the above follows:

It takes a while to actually memorize this one, but the general mnemonics is that the only prohibited option is to call a potentially modifying method (pointer receiver) on a value.

The above notion of method set gives a very formal answer to why it was not possible to even put

the val variable into an interface object, – yet leaves the reason behind this decision unknown.

Value inside an interface is not mutable at all

The Golang FAQ gives the following (italic mine):

This distinction arises because if an interface value contains a pointer *T, a method call can obtain a value by dereferencing the pointer, but if an interface value contains a value T, there is no safe way for a method call to obtain a pointer. (Doing so would allow a method to modify the contents of the value inside the interface, which is not permitted by the language specification.)

— From Golang FAQ (“Why do T and *T have different method sets?”)

I could not find this prohibition in the Go specs (maybe you could? Please drop me a line). However, one can make an illustrative usecase which, I believe, led to such prohibition. The point is the fact that typically, interfaces are used to be passed as arguments into another function (let’s call it “processor”) to abstract processor away from actual objects stored in the interface. In the above (otherwise non-compiling, but let’s imagine for a second) example

var val T = T{}

callPointerMethodOnInterface(val)

the intention of calling pointer method could (with high confidence – otherwise why use pointer method!) be to modify the object.

Go interfaces hold copies: And here comes the cornerstone: an implicit creation of the

PointerMethodCaller

interface which happens when passing argument, actually copies val object! Hence any method calls inside the

callPointerMethodOnInterface() would be performed on a copy of val and are lost on the original object.

So the fact is, interface type is no magic – it does not magically bind to the object (think C++ references which can be

bound to objects or Python “everything-by-reference” paradigm), but rather store a copy of it. Let’s check it using reflect

package which allows to inspect which value is stored in the interface:

var (

v T = T{i: 0} // Note zero here

iv ValueMethodCaller = v

)

v.i = 10 // Changing the original object

fmt.Printf("Original value: \t%#v\n", v)

fmt.Printf("Interface value: \t%#v\n", reflect.ValueOf(iv))

produces

Original value: main.T{i:10}

Interface value: main.T{i:0} <-- this one is left unchanged.

From the above, one can at least see why the interface objects holding values are protected from being mutated: it would just make no sense to mutate the interface value in the main usecase for interfaces – passing into the function.

Interfaces and addressability: Such protection against mutation comes in a form of the notion of “addressability” (see here). In short, Go takes the liberty to hide certain entities from the programmer – in the sense that the latter can’t get a pointer to them. And the value stored inside an interface belongs to that cohort; in other words, in is non-addressable.

When one writes, for example

var (

x int = 10

px *int = &x

)

it is guaranteed that the memory occupied by the variable x will be there for the lifetime (Go does memory management

on its own and guarantees that) of px and hence the pointer px will always point to int. All the types remain consistent.

Unlike those addressable variables, interface variable is by its nature something that can be reassigned to hold an object

of completely different value type – of course, so long as this new object implements this interface. For example (remember that

empty interface{} is implemented by any value3):

var (

x int32 = 0

y float32 = 10.0

)

var iface interface{} = x

fmt.Printf("Interface value: \t%#v\n", reflect.ValueOf(iface))

// Trying to take address of the value. This will not compile, but imagine it were here

// var px *int32 = &reflect.ValueOf(iface)

iface = y

fmt.Printf("Interface value: \t%#v\n", reflect.ValueOf(iface))

if that commented-out line were there, pointer px would end up in an inconsistent state, because

it points to some memory location now occupied (I hypothesize here, because we’ll see in the next section that

it is up to the particular Go implementation how to manage values in the interface) by float32, not int32 as originally.

Summarizing the above: non-addressability of the interface type protects from type inconsistencies which would have been made possible if addressing had been allowed.

Root of all the confusion – why do interfaces hold copies?

So far, we summarized usecases which would lead to inconsistent or unexpected behavior. However, all of that holds so long as interfaces hold copies of the objects. So a legitimate question persists: why are interfaces designed in such a way? Why can’t they bind to objects and thus eliminate all those numerous confusions? I could not find a definitive answer, but based on the available information I could draw some conclusions.

Because it was an implementation detail in early days

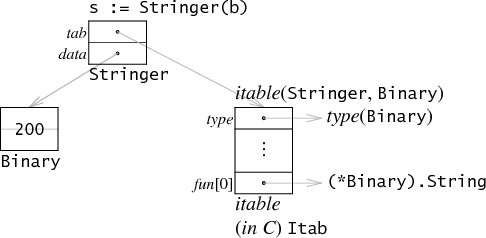

As this blog post by Russ Cox clarifies, the interfaces were designed early on to be a lightweight structure holding (along with type information) a pointer to the actual variable. I bring here a picture from his blog post

The variable s is interface, holding a pointer to actual value Binary. Credit of Russ Cox.

Let’s check what happens if one just replaces one simple value in the interface by another simple value:

var iface interface{} = (int32)(0)

// This takes address of the value. Unsafe but works. Not guaranteed to work

// after possible implementation change!

var px uintptr = (*[2]uintptr)(unsafe.Pointer(&iface))[1]

iface = (int32)(1)

var py uintptr = (*[2]uintptr)(unsafe.Pointer(&iface))[1]

fmt.Printf("First pointer %#v, second pointer %#v", px, py)

outputs

First pointer 0x10f00fc, second pointer 0x10f0100

It turns out, that every assignment to the interface changes the memory into which the value will be stored. The way interface stores this copy is just completely unreliable. This explains that the passage from the FAQ above

there is no safe way for a method call to obtain a pointer

is justified by this implementation detail.

Because Go is designed for simplicity – reference behavior is unwanted

In the end of the day, let’s face it: one could have designed a structure which allows taking the pointer of the underlying value – an doing it safely, via all the indirections. This mechanism is well-known to C++ programmers: references. In C++, writing

int x = 10;

int& y = x; // `y` is full representative everywhere.

// E.g. this line will print same addresse.

cout << &x << " " << &y << endl;

although is useless from practical prospective, yet creates y, a full “avatar” of the variable x, which binds to it,

allows taking its address directly, behaves like x and even extends its lifetime if necessary.

Same could have been done with interface values. However, let’s ask how often does one use this reference feature in C++ to mutate object (i.e. not in const-reference context)? Many production code style guides (and all the ones I’ve dealt with) would, unless for specific library-like usecases, prefer pointers over references primarily for the reason of better readability: for example, it’s much easier to tell what a call does if it is formulated in terms of pointers rather non-const references, compare

foo(val); // unclear, if val is non-const reference or const-reference, or by value?

bar(&val); // clear that something will be mutated

So I’d take liberty and speculate here that the main and final reason for non-reference-binding behavior we have observed is to keep Go simple and have everything done by value. References just don’t exist in Go, because it feels like unnecessary complication.

One can send me here to the beginning of my post where we started exploring the syntactic flexibility of the language, which exactly contradicts the argument of “readability” – and I’ll agree. It feels like Go is not always consistent4 and the whole story of this blog and numerous confusions stem from this fact.

Summary

- With ordinary variables, Go allows calling “everything on everything”:

pointer.pointerMethod(),pointer.valueMethod(),value.valueMethod()andvalue.pointerMethod(). Mechanisms engaged are selectors and automatic dereferencing. - With interfaces, it is prohibited to assign value to an interface which has pointer methods.

- The above behavior is formally regulated by the notions of method sets and addressability. Value type does not belong to pointer method sets because there value inside an interface is not addressable.

- In turn, reason for such behavior is Go’s implementation of “interface by value” – interface always holds a copy, hence calling pointer method on a copy does not make much sense for the purposes of modifying the original caller.

- In addition, there’s a reasoning around type consistency when taking a pointer of the interface value.

- It seems that the decision to keep “interface by copy” is a manifestation of a more general paradigm “no references, everything is a copy, deal with it”.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Corentin Perret-Gentil for valuable pre-publish review comments on this, Dragan Dulic and Jinwook Jeong for catching typos.

If one declares

Tastype T struct{}the copying will not happen and all the four addresses will be the same!

↩︎Value created main.T{} with address 0x119e400 Pointer created on main.T{} with address 0x119e400 Value method called on main.T{} with address 0x119e400 Pointer method called on main.T{} with address 0x119e400For careful readers - naming interfaces like

ISomethingis not idiomatic in Go. As Effective Go states itBy convention, one-method interfaces are named by the method name plus an -er suffix or similar modification to construct an agent noun: `Reader`, `Writer`, `Formatter`, `CloseNotifier` etc.

↩︎Meme time (credit of Corentin for pointing to it):

↩︎

We have not even mentioned yet that just out of the blue, Go allows taking address of temporaty objects like struct literals:

var pointer *T = &T{}which, while convenient, is explicitly called “exception” in specs and generates a lot of confusion. ↩︎

Want to discuss anything? Comments are welcome via e-mail alexey@gronskiy.com, Telegram @agronskiy or any other social media.